A promise is a promise and here is the first article on the history of Schnitzer BMW. We are not going to do it chronologically but pick out random years or periods. And the first one is perhaps a little atypical with the year 1997, when Schnitzer was sent out by BMW Motorsport to the FIA GT Championship and the 24 Hours of Le Mans with the McLaren F1 GTR Longtail.

It was a bit of a surprise that a typical touring car team like Schnitzer was chosen for this. In the past 10 years, they had only worked with the M3 E30 and the 320i Supertourer. The change from these to a McLaren F1 is already enormous and it was really not the intention to increase the starting field. BMW wanted results! It had already sent the Italian Bigazzi team into the field in 1996 to compete in the 24 Hours of Le Mans. However, that did not turn out as planned. The other McLaren teams were clearly better prepared than the Italians and that was not really the intention.

In 1995 and 1996, the McLaren F1 GTR was the reference in the then BPR championship. BPR stood for the gentlemen: Barth, Peter and Ratel who, in 1994, had invented a formula to organise GT races for gentleman drivers. The success was enormous from the beginning with a lot of interest and beautiful GT cars driving long distance races. From 1995 onwards, the Mclaren F1 GTR entered the race and humiliated the competition of Porsche and Ferrari. The latter even quit at the end of 1996 but Porsche could hardly handle their defeat. They were given permission by their management to build a 911 with a central engine (from the group C model 962). One problem: the regulations stated that the racing car had to be derived from a serial model, which was not available in 1996. They only had the racing version. Porsche was granted permission to compete in the BPR with this monster in mid-1996 and even with a factory team and its top pilots such as Stuck, Boutsen, Wollek and Dalmas. They were, however, not eligible for championship points. Naturally there followed protests from disgruntled private GT teams but these were not followed up. The Porsche 911 GT1 was in its turn, and that was no surprise, too fast for the McLaren F1. Meanwhile, the other colleagues from Stuttgart had also started working on a similar monster based on their Mercedes CLK. For the first test drives, they even had a McLaren F1, which they had rented from a French team, equipped with their own mechanics.

The BPR Championship had become extremely popular in three years and was a thorn in the side of the FIA and Bernie Ecclestone. They wanted a piece of the pie and from 1997 the championship was organised with an FIA label and a corresponding world title. This was also the end of the trio Barth/Peter and Ratel. Patrick Peter wanted the championship to remain reserved for his gentleman pilots but especially Jürgen Barth, as the big man of the Porsche Racing customer service, saw this differently. He convinced Ratel to stay and take over the organisation in the name of the FIA. The FIA-GT championship was born.

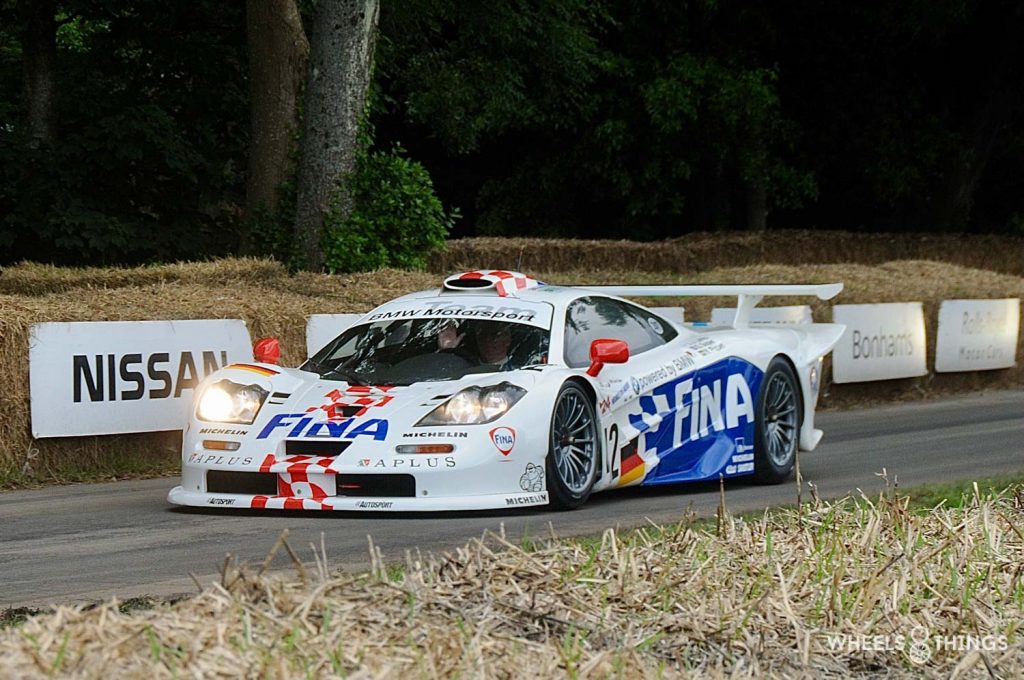

With all the new power from Porsche and Mercedes, the McLaren F1 GTR had been knocked off its throne as the best street-derived GT. Gordon Murray was forced to make an update of his successful model. This happened against his will because Murray was from the start not in favour of using the F1 as a race car. He also had to look for more downforce and this, according to the designer, was at the expense of the sheer beauty of his original design. The F1 GTR became longer, wider and 100 kg lighter than its predecessor. It was given the name “Longtail”. Besides McLaren, BMW Motorsport also did its part in the update. Paul Rosche designed a new version of the BMW V12 where the engine capacity decreased from 6.1 to 5.9 litres. This allowed the use of a larger air restrictor. However, the standard F1 still had more power than the racing version. The weight of the V12 was also reduced by 25kg and for the first time a sequential 6 speed X-Trac gearbox was used. Murray didn’t think the street version of the Longtail was a very pretty sight and he was right. But with the high rear wing on its tail and decked out in battle colours, the racing version of the Longtail was a fine example.

BMW Motorsport ordered four copies of the new F1 GTR. Two of them ( #21 and #23 ) were destined for the FIA GT championship, which was run without ABS braking system, and two were destined for participation in the 24 hours of Le Mans with ABS braking system ( #24 and #26 ). Oil manufacturer Fina and beer brewer Warsteiner were attracted as sponsors and suddenly there were four McLaren F1 GTRs in the Schnitzer workshops. That was one more than the colleagues of GTC Gulf who had bought three. Team Parabolica provided the seventh and final GTR. Schnitzer pilots on duty were JJ Letho and Steve Soper on the first car ( start number 8 in FIA GT ) and Roberto Ravaglia and Peter Kox on the second ( start number 9 ). JJ Letho, ex-Formula 1 pilot and 1995 Le Mans winner, was roped in as the new top driver. He explicitly asked to form a team with the touring car driver Steve Soper. Roberto Ravaglia, for twelve years a fixture at Schnitzer, was paired with the young Dutchman Peter Kox. He had contested some races with the West McLaren of Thomas Bscher in 1996. After a victory in the Nürburgring round he was promoted to the factory team.

The men of Charly Lamm are ready for the battle for the world championship. The first appointment is at the beginning of April in Hockenheim. It is already a “home match” for the three German manufacturers. All races for the FIA GT championship, with the exception of the Suzuka race, now last 3 or 4 hours.

McLaren appears with two cars from the official Schnitzer team and GTC brings three Gulf versions to the start. Mercedes does it with two of its new CLK GTR models and it is Porsche that provides the largest number of 911GT1s: one factory car and six private cars. Porsche had in fact offered its 911 GT1 for customer teams during the winter. They went out smoothly as this was the new reference in GT racing at the end of 1996. Furthermore three Panoz GT1’s and a new Lotus Elise GT1. The starting field was further filled up with GT2 cars from the smaller class such as the normal Porsche 911 and the Dodge Viper. Here and there we still found a gentleman driver, but from 1997 most of the cars were manned by professional drivers. The good old days of the BPR, especially for the top teams, seem to be over now.

Mercedes top driver Bernd Schneider puts his CLK on pole just in front of the McLaren of JJ Letho. Third place is for the Gulf McLaren of Gounon just in front of the second Mercedes of Allesandro Nannini. Mercedes and McLaren BMW are on the ball. Where the Porsche, a few months ago, was still the reference in GT, it immediately became clear that there was still some work to be done there. Even the factory Porsche of Hans Stuck and Thierry Boutsen could not keep up. Porsche has meanwhile been working on an Evo model for the 24 hours of Le Mans. After the start Letho immediately takes the lead before Nannini. Schneider suffers from brake problems quite soon. Five laps later he has to retire his Mercedes. The Schnitzer McLaren of Kox also has to retire with a defective gearbox. The same problem also caused the retirement of the Mercedes of Nannini. Letho and Soper have a problem free race and win with one and a half minute lead or their Gulf colleagues Gounon and Rafanel. Nielsen and gentleman driver Bscher, also Mclaren, complete the podium in front of the works Porsche of Stuck and Boutsen. At Porsche they are not really satisfied. Their customers who bought a 911GT1 are not euphoric either, as they all finish one after the other on places six to nine. They had paid a lot of money for their new car and they all end up three and four laps behind. Not really what they expected.

Gordon Murray, despite getting the full podium, was not really satisfied either. The concept of the Mercedes CLK was difficult for him because, firstly, there was no production car and, secondly, the car did not comply with the regulations, in his opinion. He immediately wanted to make an official complaint to the FIA. Big boss Ron Dennis was not keen on this. Mercedes had become the engine supplier of his Formula 1 team since 1995. After a difficult debut, that train was finally getting going with the first positive results. He absolutely wanted that relationship to remain intact and Murray was not allowed to complain.

For the second race in the championship, we head to the Silverstone circuit. In the period between Hockenheim and Silverstone, the Mercedes and Porsche teams had worked hard on their cars. Mercedes was looking for reliability and Porsche for extra speed. Bernd Schneider with his Mercedes is again the fastest in the qualifications but on the second place we see the rather surprising Panoz of David Brabham. Nice performance for the private team of Don Panoz. Both Schnitzer cars occupy the second row of the grid. Schneider immediately takes command after the start until heavy rain disrupts the race with the necessary chaos as a result. Slips and slides occur in all corners of the circuit. The Schnitzer drivers managed to bring their cars safely to the box and the pit crew did a perfect job. Both Schnitzer McLaren’s come in on places one and two in the standings. Wurz who had taken over from Schneider has fallen back several places. After a safety car period the race, on a very wet racetrack, is restarted. The Schnitzer boys are running their laps perfectly. Kox on P1 and Soper on P2. Behind them Wurz has started to catch up. The Bridgestone tyres are in these circumstances clearly better than the Michelin tyres. Through their rain experience in Japan, Bridgestone has a “Typhoon” rain tyre in its range. And that was the right tyre for these conditions. The rain continues to pour down and after a serious accident with a private McLaren, the race is red flagged. Kox and Ravaglia win before Schneider/Wurz and Letho/Soper. A second Schnitzer victory and two cars on the podium! It could hardly have been better.

Two weeks later, Helsinki is the venue for the third race. The narrow street circuit was built around the harbour of the Finnish capital. Some drivers, like Schneider and Letho who came from the DTM, already had experience with the circuit. DTM had been its guest twice in 1995 and 1996. Porsche had been granted permission by the FIA to use slightly more turbo pressure, but only the private teams could benefit from this as the works team was not present. The starting field was also rather limited after the chaos race in Silverstone with only twenty starters. Many teams were still in the process of repairing the debris on their cars. Without Porsche, it is a duel between Schnitzer and AMG. Letho is already a fish in the water on the narrow track and puts his McLaren on pole before Schneider’s Mercedes. The race is started under safety-car because the track is too narrow in the first two corners for a normal start procedure. The McLaren of Letho takes the lead and remains there for three hours. Colleague Kox has to park his car after 12 laps with a broken differential. The Mercedes of Schneider falls by the wayside after a collision with a wall and team mate Nannini has to give up with a defective gearbox. Soper and Letho win with three laps ahead of the private Porsche of Kelleners and Ortelli. Nielsen and Bscher finished third in their Gulf Mclaren. Three out of three for Schnitzer. Who would have thought it? A touring car team that immediately makes a big impact in GT racing.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans does not count towards the championship, but all the major teams, with the exception of Mercedes, will be there. Schnitzer is using two different chassis for this race. Soper and Letho will use #24R, and Kox and Ravaglia will have #26R at their disposal. Both are equipped with an ABS braking system which is allowed in the 24 hours. The other McLaren teams, who don’t have this luxury, have to rebuild their cars and equip them with ABS. All the McLaren’s are also equipped with other headlights which should provide more light in the night. On car number 42 Letho and Soper will be joined by three-time F1 world champion Nelson Piquet. Not just anyone. Piquet has always maintained good contacts with BMW after his active career and still regularly participates, for fun, in beautiful races like the 24 Hours of Francorchamps or Le Mans. It is the first time that a Schnitzer car wears the number 42. In Le Mans you are assigned a number, you don’t choose it yourself. This number, idem for 43 by the way, will always appear on their cars later when there is a free choice. Also in their last race in 2020, “42” will unfortunately be the starting number of their M6 GT3. The team of Kox and Ravaglia is reinforced by ex-Le Mans winner Eric Hélary.

In addition to the GT cars, Le Mans will feature prototype cars such as the: TWR Porsche of Joest, the Ferrari 333 SP, Courage C41 ( with Mario and Michael Andretti at the wheel among others ) and the Kremer Porsche K8. These are slightly faster than the GT cars but have a smaller petrol tank. In this way the ACO tries to ensure a balanced battle. Porsche will run its 911 GT1 Evo for the first time and is so confident that this year they are no longer providing factory support to last year’s winning Joest team. There is also a new GT participant with Nissan. Nismo, in collaboration with TWR, is bringing three units of its new R 390GT to the start. All equipped with top drivers like our own Eric Van de Poele. And what is in the paddock? A road legal R390. In Japan, they had clearly done their homework better than Mercedes and Porsche!

For Schnitzer, it is not really a debut at Le Mans. That took place in 1972 when Hans Heyer and René Herzog drove a “simple touring car” BMW 2800 CS among the big boys from Matra, Porsche, Ferrari and Alfa Romeo. In 1976 they came back again with their BMW 3.5CSL Gösser Beer with Dieter Quester, Albrecht Krebs and our own Alain Peltier. In both participations they did not see the finish line, but those were totally different times. A small private team, half of which was made up of volunteers, took part in the biggest endurance race in the world. In 1997, the workforce was over 50 highly qualified and trained employees. What a difference!

In the qualifications, ex-Formula 1 pilot Michele Alboroto takes pole position with his Joest TWR Porsche. Boutsen follows with the 911 GT1 and a surprising third is Eric Van de Poele with his new Nissan R390GT1. Letho puts the Schnitzer 42 in fourth place ahead of the second Porsche 911 of Collard. Once again Schnitzer delivers the fastest McLaren.

We see a beautiful first part of the race. Besides the top 5 from the qualifications, the Momo Ferrari of Theys and the other Nissan’s and McLaren’s are also getting involved in the front debates. Unfortunately the Nissan’s all three disappear with overheating problems at the rear axle. Problems also arise at Schnitzer: the 42 has a water leak and has to continue for another 8km to reach its box. Pilot Soper thinks it is the end of the race. Without water and with an overheated engine, he fears for the worst. The mechanics have a different idea and after 38 minutes the repaired McLaren is back on the track. A true feat. The V12 engine has apparently not suffered from the heat. Soper falls back from third to twenty-sixth place. He will fight his way back, with Letho and Piquet, to eighth place at 8am Sunday morning. JJ Letho is now at the wheel but puts the “42” into the wall in the slowest corner of the circuit. To this day, JJ still does not understand how he managed this. He made it back to the box but there was a lot of damage at the front. Gordon Murray decides, after having examined the chassis, that it is too dangerous to continue and this is the end of the race. The “43” has a slightly slower pace than the “42”. There are also problems with the Michelin tyres, which do not work as well as on the other car. During the night, the compound is changed and it seems to go much better. Kox/Ravaglia and Hélary battle with their Gulf colleagues for a place of honour. At the front, the factory Porsches are in the lead with Stuck/Boutsen/Wollek on P1 and Collard/Dalmas/Kelleners on P2. The ACO regulations provide for a little more freedom for the Porsche GT1 and this is clearly noticeable. Third place is for the TWR Joest Porsche of Alboreto/Kristensen and Johansson.

Drama at Porsche: leader Wollek, who has been driving behind an Mclaren for several laps, tries to overtake it, but runs off the track during the overtaking manoeuvre. He still tries to drive to the box but has to park his 911 GT1 with a broken transmission. Fortunately for Porsche his team mates take over and remain in the lead for 5 hours until at 13:39hrs flames appear from under the bonnet of the Porsche. Pilot Kelleners immediately parked the car at a fire station. The firemen who had rushed to the scene were able to prevent the Porsche from going up in flames. Some Porsche’s had to abandon the race due to overheating of the engine. This was probably also the case here.

An accident never comes alone, for twenty minutes later the same fire brigade is again on hand to extinguish a McLaren: the Gulf of Bellm/Sekiya and Gilbert Scott, driving in fourth position. The latter parks the F1GTR, with an even bigger blaze, on the same spot as the Porsche. The TWR Joest Porsche now takes the lead, shortly followed by the Gulf McLaren of Raphanel/Gounon and Olofsson. The Schnitzer follows in third place. This situation remains unchanged and two ex-Formula 1 pilots Michele Alboreto and Stefan Johansson win the 1997 24 Hours of Le Mans with “rookie” Tom Kristensen. The Gulf McLaren follows one lap down on P2 but wins the GT classification. Kox/Ravaglia and Hélary are third by 3 laps. On the fourth place follows a Courage proto with 25 laps behind. All in all, a good result for Schnitzer who, after dropping out of the 42 car, had to give way to the GTC Gulf McLaren team for the first time in this race.

Two weeks later, there is another race for the FIA GT championship at the Nürburgring. Mercedes was not at Le Mans and had worked hard to improve the reliability of its CLK. They had even built a third car that will now join the starting field. At BMW in Munich the bosses, in spite of their three victories in three races and an ample lead in the points classification, were not really satisfied with the state of affairs in the FIA GT championship. After first Porsche and then Mercedes had come up with a model for which no street car existed, they had decided to quit GT racing at the end of the season. As an alternative, they decided to develop their own LMP proto with the already existing V12 engine. Planned debut: The 1998 24 Hours of Le Mans. As a sign of their displeasure, they had also fitted both Schnitzer cars with two German number plates as a protest. M GT 8 for Letho and Soper, M GT 9 for Kox and Ravaglia. An original sight though. For circuit racing cars with a number plate we have to go back to the sixties anyway. At that time many cars were still driven on public roads to the circuits. The number plates usually stayed on the cars during the races.

Bernd Schneider is again unapproachable in the qualifications and puts his CLK on P1. Letho is able to squeeze himself in between the Mercedes and can start on P2. But it is immediately clear that Mercedes is very strong at the Nürburgring. Letho can’t keep up with the Mercedes pace and has to slowly drop out of the leading group. The Mercedes trio took over. The two Schnitzer McLaren’s follow at a small distance. Porsche, after their fine performance in Le Mans, is again no match for Mercedes and McLaren BMW. Schneider and Ludwig achieve a first and even rather easy victory before their team mates Nannini and Tiemann. Then follow the two Schnitzer McLaren’s with one lap behind. Letho and Soper finish third, Kox and Ravaglia fourth. Mercedes has started the overtaking hunt.

Francorchamps is the next stop of the FIA GT championship. And that is familiar territory for Schnitzer. Here they achieved in the past their greatest successes during the 24 hours for tourism cars with the 635CSi and the M3. In thirteen entries, there were five wins, three P2 and two P3. No one else can present these figures. Letho is clearly aware of this history and, against all odds, puts his McLaren on pole ahead of three Mercedes CLKs. At the start, however, he has to leave Schneider behind, who has a slightly better line to take at the Radillon. In the Gulf camp, they are having a very bad day: Jean Marc Gounon is fighting with Thierry Boutsen’s Porsche but runs off the track, starts spinning and collides with the two other McLaren’s of the Gulf GTC team. The three Longtails remain, after half a lap, next to the track. A great pity for the team and the spectators present.

Letho also has to let the second Mercedes pass him but he continues to follow the leading duo. Thierry Boutsen has to put his 911GT1 to the box with steering problems. A retirement follows a little later. Meanwhile, there is a cloudburst at the back of the track. This creates a difficult situation with a half dry and a half wet track. Both Mercedes cars go off the track but can continue their race. Letho takes the lead and in these conditions he is unbeatable. Mercedes is also unable to take full advantage of its super “Typhoon” Bridgestone rain tyres in this scenario: they gain time on the wet but lose too much on the dry. Letho drives two minutes away from his Mercedes colleagues! After the pit stop, Steve Soper takes over but a loosened base plate causes problems for the McLaren. Schneider starts to catch up. The second Mercedes has to go to his box with shifting problems and loses more than ten laps. The second Schnitzer McLaren is on the way to the podium but a collision with a Porsche, from the smaller class, causes loss of time. Schneider comes closer and closer to Soper but suddenly the clock stops. Soper is, despite his loose floor plate, again a bit faster and drives to victory. Schnitzer, BMW, Letho, Soper and Charly Lamm get the most beautiful victory of the year. They beat a faster opponent, in a direct and hard fought duel, in very difficult conditions. Bob Wollek and Yannick Dalmas finished third, just ahead of the second Schnitzer McLaren.

The hills of Francorchamps are exchanged for the slightly bigger mountains of the Styrian region. There the new A1 Ring, formerly the Österreichring, hosts the next race. The Schnitzer team will now use chassis #26R for Letho and Soper. #26R is the Le Mans car of Kox and Ravaglia that was converted to FIA regulations. The second Le Mans car was already sold to the Gulf team after the 24 hours race to replace one of their burnt-out cars. The race is much less exciting than in Spa. Mercedes is the master here. All three storm away after the start flag. There is a commotion at the pit stop of the leading Bernd Schneider: the CLK refuses to start due to an electrical problem. This is repaired but they lose several laps and also the possibility of victory. Bernd Schneider, to the dismay of his opponents, is thus transferred to another CLK for the second time. He will win together with Ludwig and Maylander. At the end of the race, Letho and Soper were able to work their way up to second place. Unfortunately, Soper has to make an unexpected pit stop to reattach a loose wheel. This caused them to fall back to third place behind the Mercedes of Nannini and Tiemann. The other Schnitzer McLaren had to abandon the race after a collision.

To be able to bear the status of a world championship, it is necessary for races to be contested on several and preferably as many continents as possible. One of the intercontinental trips was the 1000 km of Suzuka. Suzuka is not unknown territory for Schnitzer. In 1994 and 1995 they participated with the 318is ( 1994 ) and 320i ( 1995 ) in the Japanese Super Tourer Championship. In 1995 Steve Soper was the champion of this series. Porsche obviously had the same advantage with their earlier participations in this competition. For AMG Mercedes it was all new territory. The 1000 km of Suzuka traditionally take place in the Japanese “hot” summer. Ludwig put his CLK on pole ahead of the surprising Porsche 911GT1 of Dalmas. The Porsches, which now have a sequential gearbox, are clearly faster. In the race, it is again the three CLKs who take the lead. Porsche and McLaren follow at a small distance but cannot threaten the Mercedes. Both 911 GT1’s quickly retire with problems with their new sequential gearbox. Leader Wurz also has to go to the pits for the repair of a broken suspension. At Mercedes, a new game of musical chairs begins. Schneider moves to the car of Nannini and Tieman. After the Mercedes duo GTC Gulf with Rafanel/Gounon and Olofsson and Schnitzer with Leto and Soper fight for the third place on the podium. Schneider wins once again due to a car change. The grumbling in the paddock begins to escalate. The Gulf McLaren finishes third ahead of Schnitzer. This race was not really exciting but we have to note that the first four cars finished in the same lap. The time difference between P1 and P4 was just under two minutes and that is not a big difference after a 1000 km race!

After the Eastern trip, the teams head to Donington, England. Schneider’s “car swap” with Mercedes was a problem for many teams. The FIA was also annoyed with the problem and proposed to ban this from now on. The condition was that all teams present agreed with the measure, including Mercedes. The proposal was that the crew of each car, after the warm-up on Sunday morning, would be definitively fixed. Groans from Norbert Haug, Mercedes team principal. However, the pressure was so great that he was on his own and had no choice but to give in. Afterwards he showed his displeasure. Apparently Norbert had forgotten that he still could not offer a street-version of his CLK and that they were driving a non-compliant car. Schneider could keep all his points, he only had to choose the right car from now on. The battle for the championship was becoming very exciting.

Mercedes is again the fastest in qualifying with a full front row on the grid. P3 is for a Schnitzer McLaren. This time it is not Letho who takes care of this but Roberto Ravaglia! The three CLKs are again the fastest at the start and take the first three places. They are followed by Letho but he cannot pose a direct threat. A shake-up at the pit stops. All three CLKs come into the pit box one after the other. There is only room for two and Ludwig is sent back out immediately. Due to this tactical blunder of Mercedes, Letho comes on the third place. He will keep it until the end of the race. A few laps before the end the servo steering of the Mercedes of Schneider and Wurz breaks down. Alexander still manages to solve this hill with pure manpower and reaches the finish. The race should not have lasted much longer because without a servo it is almost impossible to make fast laps. Schneider is lucky again and becomes the new leader in the championship. Kox and Ravaglia end on P5. Ravaglia announces after the race that he will retire as a professional driver at the end of the year. He will still finish the three remaining races. This brings an end to his thirteen-year career as a BMW factory pilot. Most of this time at the wheel of a Schnitzer BMW. He won a world title, two European titles, was multiple Italian champion and also a hard-fought DTM title is on his list of honours. He drove the 635CSi, M3, 318is, 320i and ends his career with the mighty McLaren F1GTR Longtail. A beautiful farewell. In the last three races, the Schnitzer men will thank Ravaglia with a farewell message on his McLaren.

The Mugello circuit, the venue for the next race, is owned by Ferrari. Unfortunately, no Ferrari is present at the circuit in Tuscany. In qualifying, the three AMG CLKs are again the fastest. Letho is almost as fast but is stranded on P4 in front of the surprising Panoz Esperante of Bernard and Lagorge. The spectators see a boring first part of the race. The three Mercedes CLKs are turning their laps at a small distance followed by the McLaren of Letho. The race changes direction after the first pitstops and goes from boring to exciting. First Soper breaks the Mercedes dominance by passing Nannini. Shortly after, Schneider disappears from the race after a collision with Pierre Luigi Martini. Because of the new regulations he is no longer allowed to change cars. Ludwig is the new leader but he gets the same problem with his servo steering as Wurz in Donington. He has to go to the pits for repairs and will not play a significant role anymore. Nannini is now in the lead, followed by Soper. During the last pit stop they decide to change only the left tyres and not to change the drivers. At Schnitzer, they opted for a different strategy by fitting 4 new Michelin tyres to the McLaren and putting Letho back behind the wheel of the F1GTR. The loss of time which this caused is compensated by Letho in no time. He quickly overtakes Nannini and passes without any problems. The Schnitzer McLaren is now the fastest car in the race and even trails the AMG Mercedes by 35 seconds. Letho and Soper win their fourth race of the year ahead of Nannini and Tiemann. Third and fourth place are for Porsche with Dalmas/Wollek on three and Boutsen/Kelleners on four. Kox and Ravaglia bring in the second Schnitzer McLaren in fifth place. Mugello was the last race in Europe. Organizer Ratel will have all equipment, including the trucks of the teams, shipped to the USA where the last two races of the year will take place in Sebring and Laguna Seca.

First up is Sebring. A mythical American circuit that hosts the annual 12 Hours of Sebring. An endurance race that, according to the participating drivers, is tougher than the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Many manufacturers test their cars at the Sebring circuit. If they can make it there, they are approved for Le Mans. The concrete track is so bumpy and rough that the cars suffer greatly. The circuit is built around the remains of an old army base. Letho’s McLaren flies over the bumps of Sebring. He easily takes the pole position before Schneider who has to give up half a second. Third is the Porsche of Dalmas. How beautiful can motor racing be? Three different brands in the first three places. Soper will take care of the first stint but has to let Schneider go first. In the battle for P1, things get heated: Schneider, Soper, Stuck and the Lister Jaguar of Baily come into contact. The latter cannot continue, the other three drop back in the rankings. Soper has a damaged tyre and has to come in for replacement. New slicks are fitted to his #026R. As he leaves the pitlane, a violent thunderstorm breaks out over Sebring and the heavens open wide. This is a few seconds too late for Soper as he has to come in again, like all the other competitors, for rain tyres. The Schnitzer McLaren loses two laps to the leader Nannini. Nannini however was unable to keep his CLK on the track and ended up in the crash barrier. Kox took over the lead with the second Schnitzer and did this perfectly in very difficult circumstances. The combination of the hard track and the rain seems to suit the McLaren very well. Most of his colleagues can’t cope with this and one by one they go off track. Schneider (with his Bridgestone Typhoon tyres) and Letho also show their skills and make up a lot of ground and climb up the rankings. Schneider passes Ravaglia, who is a bit less happy in these bad conditions, and is the new leader. Letho starts his last stint in P5 and takes over fourth place from Dalmas. He continues his hunt for the Panoz of David Brabham and Perry McCarthy ( 1st black Stig of Top Gear ) but twenty minutes before the end flames come out from under the rear of his car. Letho stops at a fire station but gets little help there. He takes the extinguishers himself and tries to control the now considerable fire until he gets help from a fire engine. End of the race and maybe end of the championship for Letho and Soper? Ludwig and Schneider win the race before Kox and Ravaglia. The third place is for the Panoz of Brabham and McCarthy who provide a good result for the American team of Don Panoz with a podium in their own country.

One week later, the next race in Laguna Seca is already on the calendar. The teams make the 4800 km trip between the two American coasts with their own trucks and arrive in sunny California. At Schnitzer, there is one burnt-out Mclaren in their trailer. #026R is, in the short term, beyond repair. Another solution must be found. The team’s third car, #021R, had meanwhile become a show model and was on display at the Tokyo Motor Show. It was removed from the BMW stand and transported to Laguna Seca. To spread the title chances, Letho and Soper were put on a different car. Letho gets Kox as a teammate and Soper will share the second car with Ravaglia. The “billiard” track of Laguna Seca is a nightmare for the Mclaren F1. The Mercedes CLK’s and even the Porsche’s qualify ahead of Letho who doesn’t get further than P5. Soper can put his F1 on P8. And it goes from bad to worse. The race becomes a true calvary for the Schnitzer team. Whilst up front Porsche can hold its own against Mercedes for the first time this year, Letho has to take his #021R to the box after twelve laps with a water leak. Recovery is not an option and the retirement is a fact. Now only Soper can go for the championship, but his pace is not fast enough. It is even completely over when team mate Ravaglia, in his very last race, comes into contact with a Porsche from the small class. They are able to continue their race and finish on P11, just outside the points. At Porsche they finally play for victory but due to a small problem with a pit stop Mcnish and Kelleners have to let the Mercedes of Schneider and Ludwig take the victory. This makes Bernd Schneider the FIA GT Champion of 1997.

BMW had already decided to leave the FIA GT championship after this race. Schnitzer can leave with their heads held high. They bring the vice-title and five victories to their home bases in Freilassing and Munich. They were only beaten by an “illegal” car and a pilot who, for more than half the year, jumped from one car to another. The first street version of the Mercedes CLK GTR will only be built at the end of 1998, two years after the first racing CLK made its racing debut. Schnitzer, with its Mclaren’s, is actually the moral winner of the 1997 World Cup. Even the switch from the BMW 320i Supertourer to the Mclaren F1 went without a hitch, it even seemed as if they had never done anything else. From the beginning the team was at the top. For 1998 they go back in the other direction. BMW Motorsport sent Schnitzer, with the now “old” 320i E36, to the German Super Tourenwagen Championship to compete with Peugeot, Opel and Audi. What the Italian colleagues of Bigazzi failed to do in 1996 and 1997 Schnitzer and Johnny Cecotto did in 1998 by winning the German championship title. The BMW E36 could then enjoy a well-earned retirement.

The 1997 FIA GT campaign will lay the groundwork, however, for what will become their greatest victory later in 1999 with the BMW V12 LMR in the 24 Hours of Le Mans. More on this in a later article.

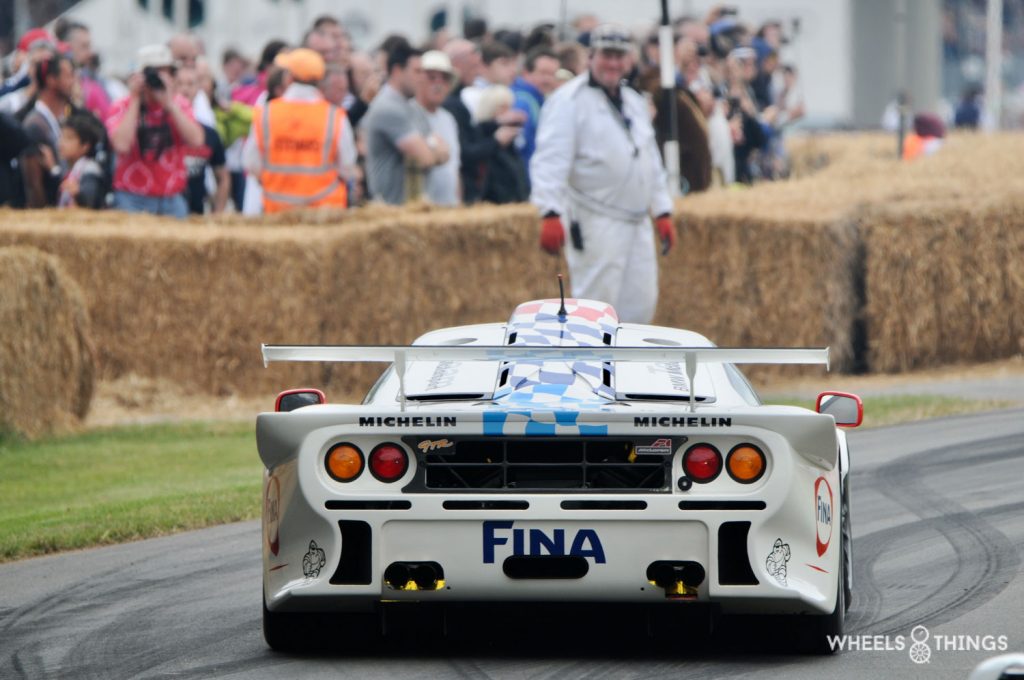

The Mclaren disappears from the workshops in Freilassing. #26R goes to the BMW Classic collection and regularly comes out for big events like Le Mans Classic or the Festival of Speed at Goodwood. It is just a little strange that #26R was fitted with the bodywork of #24R. The number 42 and the names of Piquet, Letho and Soper appear to be worth more than Ravaglia and Kox. #24R was sold to a private English team and in 1998, with O’Rourke, Sugden and Auberleen, finished a magnificent fourth in the 24 hours of Le Mans. The other two cars were sold to private collectors. One of these is Lawrence Stroll, the current owner of the Aston Martin Formula One team. Three of the four F1s are still in their 1997 Schnitzer BMW Fina version. Only #24R is in its 1998 Emka Le Mans version.

The FIA GT championship will experience its swan song in 1998. Only Porsche and Mercedes take part and even have to provide extra cars due to a lack of participants. It was of no avail as it was disbanded at the end of 1998. From 1999 only cars from the smaller GT class will be allowed. With this new formula, the FIA GT championship will revive and experience great moments.

Article & photos: Joris de Cock